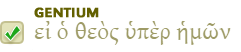

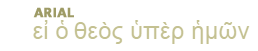

It is often stated by theologians of the Reformation period that μετάνοια and μεταμέλεια, with their several verbs, μετανοεῖν and μεταμέλεσθαι, are so far distinct, that where it is intended to express the mere desire that the done might be undone, accompanied with regrets or even with remorse, but with no effective change of heart, there the latter words are employed; but where a true change of heart toward God, there the former. It was Beza, I believe, who first strongly urged this. He was followed by many; thus see Spanheim, Dub. Evang. vol. iii. dub. 9; and Chillingworth (Sermons before Charles I. p. 11): ‘To this purpose it is worth the observing, that when the Scripture speaks of that kind of repentance, which is only sorrow for something done, and wishing it undone, it constantly useth the word μεταμέλεια, to which forgiveness of sins is nowhere promised. So it is written of Judas the son of perdition (

Let me, before proceeding further, correct a slight inaccuracy in this statement. Μεταμέλεια nowhere occurs in the N. T.; only once in the Old (

Μετανοεῖν is properly to know after, as προνοεῖν to know before, and μετάνοια afterknowledge, as πρόνοια foreknowledge; which is well brought out by Clement of Alexandria (Strom. ii. 6): εἰ ἐφ᾽ οἷς ἥμαρτεν μετενόησεν, εἰ σύνεσιν ἔλαβεν ἐφ᾽ οἷς ἔπταισεν, καὶ μετέγνω, ὅπερ ἐστὶ, μετὰ ταῦτα ἔγνω· βραδεῖα γὰρ γνῶσις, μετάνοια. So in the Florilegium of Stobaeus, i. 14: οὐ μετανοεῖν ἀλλὰ προνοεῖν χρὴ τὸν ἄνδρα τὸν σοφόν. At its next step μετάνοια signifies the change of mind consequent on this after-knowledge; thus Tertullian (Adv. Marcion. ii. 24): ‘In Graeco sermone poenitentiae nomen non ex delicti confessione, sed ex animi demutatione, compositum est.’ At its third, it is regret for the course pursued; resulting from the change of mind consequent on this after-knowledge; with a δυσαρέστησις, or displeasure with oneself thereupon; ‘passio quaedam animi quae veniat de offensâ sententiae prioris,’ which, as Tertullian (De Poenit. 1) affirms, was all that the heathen understood by it. At this stage of its meaning it is found associated with δηγμός (Plutarch, Quom. Am. ab Adul. 12); with αἰσχύνη (De Virt. Mor. 12); with πόθος (Pericles, 10; cf. Lucian, De Saltat. 84). Last of all it signifies change of conduct for the future, springing from all this. At the same time this change of mind, and of action upon this following, may be quite as well a change for the worse as for the better; there is no need that it should be a ‘resipiscentia’ as well; this is quite a Christian superaddition to the word. Thus A. Gellius (xvii. 1. 6): ‘Poenitere tum dicere solemus, cum quae ipsi fecimus, aut quae de nostrâ voluntate nostroque consilio facta sunt, ea nobis post incipiunt displicere, sententiamque in iis nostram demutamus.’ In like manner Plutarch (Sept. Sap. Conv. 21) tells us of two murderers, who, having spared a child, afterwards ‘repented’ (μετενόησαν), and sought to slay it; μεταμέλεια is used by him in the same sense of a repenting of good (De Ser. Num. Vin. 11); so that here also Tertullian had right in his complaint (De Poenit. 1): ‘Quam autem in poenitentiae actu irrationaliter deversentur [ethnici], vel uno isto satis erit expedire, cum illam etiam in bonis actis suis adhibent. Poenitet fidei, amoris, simplicitatis, patientiae, misericordiae, prout quid in ingratiam cecidit.’ The regret may be, and often is, quite unconnected with the sense of any wrong done, of the violation of any moral law, may be simply what our fathers were wont to call ‘hadiwist’ (had-I-wist better, I should have acted otherwise); thus see Plutarch, De Lib. Ed. 14; Sept. Sap. Conv. 12; De Soler. Anim. 3: λύπη δι᾽ ἀλγηδόνος, ἣν μετάνοιαν ὀνομάζομεν, ‘displeasure with oneself, proceeding from pain, which we call repentance’ (Holland). That it had sometimes, though rarely, an ethical meaning, none would of course deny, in which sense Plutarch (De Ser. Num. Vin. 6) has a passage in wonderful harmony with

It is only after μετάνοια has been taken up into the uses of Scripture, or of writers dependant on Scripture, that it comes predominantly to mean a change of mind, taking a wiser view of the past, συναίσθησις ψυχῆς ἐφ᾽ οἷς ἔπραξεν ἀτόποις (Phavorinus), a regret for the ill done in that past, and out of all this a change of life for the better; ἐπιστροφὴ τοῦ βίου (Clement of Alexandria, Strom. ii. 245 a), or as Plato already had, in part at least, described it, μεταστροφὴ ἀπὸ τῶν σκιῶν ἐπὶ τὸ φῶς (Rep. vii. 532 b) περιστροφή, ψυχῆς περιαγωγή (Rep. vii. 521 c). This is all imported into, does not etymologically nor yet by primary usage lie in, the word. Not very frequent in the Septuagint or the Apocrypha (yet see Ecclus. 44:15; Wisd. 11:24; 12:10, 19; and for the verb,

But while thus μετανοεῖν and μετάνοια gradually advanced in depth and fulness of meaning, till they became the fixed and recognized words to express that mighty change in mind, heart, and life wrought by the Spirit of God (‘such a virtuous alteration of the mind and purpose as begets a like virtuous change in the life and practice,’ Kettlewell), which we call repentance; the like honour was very partially vouchsafed to μεταμέλεια and μεταμέλεσθαι. The first, styled by Plutarch σώτειρα δαίμων, and by him explained as ἡ ἐπὶ ταῖς ἡδοναῖς, ὅσαι παράνομοι καὶ ἀκρατεῖς, αἰσχύνη (De Gen. Soc. 22), associated by him with βαρυθυμία (An Vit. ad Inf. 2), by Plato with ταραχή (Rep. ix. 577 e; cf. Plutarch, De Cohib. Irâ, 16), has been noted as never occurring in the N. T.; the second only five times; and designating on one of these the sorrow of this world which worketh death, of Judas Iscariot (

[The following Strong's numbers apply to this section:G3338,G3340.]

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |