lxxxviii. ἱερός, ὅσιος, ἅγιος, ἁγνός.

Ἱερός, probably the same word as the German ‘hehr’Etym. Note. 37 (see Curtius, Grundzüge, vol. v. p. 369), never in the N. T., and very seldom elsewhere, implies any moral excellence. It is singular how seldom the word is found there, indeed only twice (1 Cor. 9:13; 2 Tim. 3:15); and only once in the Septuagint (Josh 6:8: ἱεραὶ σάλπιγγες); four times in 2 Maccabees, but not else in the Apocrypha; being in none of these instances employed of persons, who only are moral agents, but always of things. To persons the word elsewhere also is of rarest application, though examples are not wanting. Thus ἱερὸς ἄνθρωπος is in Aristophanes (Ranoe, 652) a man initiated in the mysteries; kings for Pindar (Pyth. v. 97) are ἱεροί, as having their dignity from the gods; for Plutarch the Indian gymnosophists are ἄνδρες ἱεροὶ καὶ αὐτόνομοι (De Alex. Fort. i. 10); and again (De Gen. Soc. 20), ἱεροὶ καὶ δαιμόνιοι ἄνθρωποι: and compare De Def. Orac. 2. Ἱερὸς (τῷ θεῷ ἀνατεθειμένος, Suidas) answers very closely to the Latin ‘sacer’ (‘quidquid destinatum est diis sacrum vocatur’), to our ‘sacred.’ It is that which may not be violated, the word therefore being constantly linked with ἀβέβηλος (Plutarch, Quoest. Rom. 27), with ἄβατος (Ibid.), with ἄσυλος (De Gen. Soc. 24); this its inviolable character springing from its relations, nearer or remoter, to God; and θεῖος and ἱερός being often joined together (Plato, Tim. 45 a). At the same time the relation is contemplated merely as an external one; thus Pillon (Syn. Grees): ‘ἅγιος exprime l’idée de sainteté naturelle et intérieure ou morale; tandis qu’ ἱερός, comme le latin sacer, n’exprime que l’idée de sainteté extérieure ou d’inviolabilité consacrée par les lois ou la coutume.’ See, however, Sophocles, Oedip. Col. 287, which appears an exception to the absolute universality of this rule. Tittman: ‘In vote ἱερός proprie nihil aliud cogitatur, quam quod res quaedam aut persona Deo sacra sit, nullâ ingenii morumque ratione habitâ; imprimis quod sacris inservit.’ Thus the ἱερεύς is a sacred person, as serving at God’s altar; but it is not in the least implied that he is a holy one as well; he may be a Hophni, a Caiaphas, an Alexander Borgia (Grinfield, Schol. in N. T., p. 397). The true antithesis to ἱερός is βέβηλος (Plutarch, Quoest. Rom. 27), and, though not so perfectly antithetic, μιαρός (2 Macc. 5:16).

Ὅσιος is oftener grouped with δίκαιος for purposes of discrimination, than with the words here associated with it; and undoubtedly the two constantly keep company together; thus in Plato often (Theoet. 176 b; Rep. x. 615 b; Legg. ii. 663 b); in Josephus (Antt. viii. 9. 1), and in the N. T. (Tit. 1:8); and so also the derivatives from these; ὁσίως and δικαίως (1 Thess. 2:10); ὁσιότης and δικαιοσύνη (Plato, Prot. 329 c; Luke 1:75; Ephes. 4:24; Wisd. 9:3; Clement of Rome, 1 Ep. 48). The distinction too has been often urged that the ὅσιος is one careful of his duties toward God, the δίκαιος toward men; and in classical Greek no doubt we meet with many passages in which such a distinction is either openly asserted or implicitly involved; as in an often quoted passage from Plato (Gorg. 507 b): καὶ μὴν περὶ τοὺς ἀνθρώπους τὰ προσήκοντα πράττων, δίκαι᾽ ἂν πράττοι, περὶ δὲ θεοὺς ὅσια.1 Of Socrates, Marcus Antoninus says (vii. 66), that he was δίκαιος τὰ πρὸς ἀνθρώπους, ὅσιος τὰ πρὸς θεούς: cf. Plutarch, Demet. 24; Charito, i. 10. 4; and a large collection of passages in Rost and Palm’s Lexicon, s. v. There is nothing, however, which warrants the transfer of this distinction to the N. T., nothing which would restrict δίκαιος to him who should fulfil accurately the precepts of the second table (thus see Luke 1:6; Rom. 1:17; 1 John 2:1); or ὅσιος to him who should fulfil the demands of the first (thus see Acts 2:27; Heb. 7:26). It is beforehand unlikely that such distinction should there find place. In fact the Scripture, which recognizes all righteousness as one, as growing out of a single root, and obedient to a single law, gives no room for such an antithesis as this. He who loves his brother, and fulfils his duties towards him, loves him in God and for God. The second great commandment is not coordinated with the first greatest, but subordinated to, and in fact included in, it (Mark 12:30, 31).

If ἱερός is ‘sacer,’ ὅσιος is ‘sanctus’ (== ‘sancitus’), ‘quod sanctione antiquâ et praecepto firmatum’ (Popma; cf. Augustine, De Fid. et Symb. 19), as opposed to ‘pollutus.’ Some of the ancient grammarians derive it from ἅζεσθαι, the Homeric synonym for σέβεσθαι, rightly as regards sense, but wrongly as regards etymology; the derivation indeed of the word remains very doubtful (see Pott, Etym. Forschung. vol. i. p. 126). In classical Greek it is far more frequently used of things than of persons; ὁσία, with βουλή or δίκη understood, expressing the everlasting ordinances of right, which no law or custom of men has constituted, for they are anterior to all law and custom; and rest on the divine constitution of the moral universe and man’s relation to this, on that eternal law which, in the noble words of Chrysippus, is πάντων βασιλεὺς θείων τε καὶ ἀνθρωπίνων πραγμάτων: cf. Euripides, Hecuba, 799–801. Thus Homer (Odyss. xvi. 423): οὐδ᾽ ὁσίη κακὰ ῥάπτειν ἀλλήλοισιν. The ὅσιος, the German ‘fromm,’ is one who reverences these everlasting sanctities, and owns their obligation; the word being joined with εὐσεβής (2 Macc. 12:45), with εὔορκος (Plato, Rep. 263 d), with θεῖος (Plutarch, De Def. Orat. 40); more than once set over against ἐπίορκος (Xenophon). Those things are ἀνοσία, which violate these everlasting ordinances; for instance, a Greek regarded the Egyptian custom of marriage between a brother and sister, still more the Persian between a mother and son, as ‘incestum’ (incastum), μηδαμῶς ὅσια as Plato (Legg. viii. 858 b) calls them, mixtures which no human laws could ever render other than abominable. Such, too, would be the omission of the rites of sepulture by those from whom they were due, when it was possible to pay them; if Antigone, for instance, in obedience to the edict of Creon, had suffered the body of her brother to remain unburied (Sophocles, Antig. 74). What the ὅσιον is, and what are its obligations, has never been more nobly declared than in the words which the poet puts into her mouth:

οὐδὲ αθένειν τοσοῦτον ᾠόμην τὰ σὰ

κηρύγμαθ᾽, ὥστ᾽ ἄγραπτα κἀσφαλῆ θεῶν

νόμιμα δύνασθαι θνητὸν ὄνθ᾽ ὑπερδραμεῖν (453–5).

Compare an instructive passage in Thucydides, ii. 52, where ἱερά and ὅσια occur together, Plato in like manner (Legg. ix. 878 b) joining them with one another. This character of the ὅσιον as anterior and superior to all human enactments, puts the same antithesis between ὅσια and νόμιμα as exists between the Latin ‘fas’ and ‘jus.’

When we follow ὅσιος to its uses in sacred Greek, we find it, as was inevitable, gaining in depth and intensity of meaning; but otherwise true to the sense which it already had in the classical language. We have a striking testimony for the distinction which, in the minds of the Septuagint translators at least, existed between it and ἅγιος, in the very noticeable fact, that while ὅσιος is used some thirty times as the rendering of חָסִיד (Deut. 33:8: 2 Sam. 22:26; Ps. 4:4), and ἅγιος nearly a hundred times as that of קָדוּשׁ (Exod. 19:6; Num. 6:5; Ps. 15:3), in no single instance is ὅσιος used for this, or ἅγιος for that; and the same law holds good, I believe, universally in the conjugates of these; and, which is perhaps more remarkable still, of the other Greek words which are rarely and exceptionally employed to render these two, none which is used for the one is ever used for the other; thus καθαρός, used for the second of these Hebrew words (Num. 5:17), is never employed for the first; while, on the other hand, ἐλεήμων (Jer. 3:12), πολυέλεος (Exod. 34:6), εὐλαβής (Mic. 7:2), used for the former, are in no single instance employed for the latter.

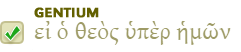

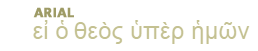

Ἅγιος == קָדוּשׁ (on the etymology of which word see the article in Herzog’s Real-Encyclopädie, Heiligkeit Gottes) and ἁγνός have been often considered different forms of one and the same word. At all events, they have in common that root ἈΓ, reappearing as the Latin ‘sac’ in ‘sacer,’Etym. Note. 38 ‘sancio,’ and many other words. It will thus be only natural that they should have much in common, even while they separate off, and occupy provinces of meaning which are clearly distinguishable one from the other. Ἅγιος is a word of rarest use in Attic Greek, though Porson is certainly in error when he says (on Euripides, Med. 750; and compare Pott, Etymol. Forsch. vol. iii. p. 577) that it is never used by the tragic poets; for see aeschylus, Suppl. 851. Its fundamental idea is separation, and, so to speak, consecration and devotion to the service of Deity; thus ἱερὸν μάλα ἅγιον, very holy temple (Xenophon, Hell. iii. 2. 14); it ever lying in the word, as in the Latin ‘sacer,’ that this consecration may be as ἀνάθημα or ἀνάθεμα (see back, page 16). Note in this point of view its connexion with ἁγής ἅγος: which last it may be well to observe is recognized now not as another form of ἄγος, as being indeed no more than the Ionic form of the same word, but fundamentally distinct (Curtius, Grundzüge, p. 155 sqq.). But the thought lies very near, that what is set apart from the world and to God, should separate itself from the world’s defilements, and should share in God’s purity; and in this way ἅγιος speedily acquires a moral significance. The children of Israel must be an ἔθνος ἅγιον, not merely in the sense of being God’s inheritance, a λαὸς περιούσιος, but as separating themselves from the abominations of the heathen nations round (Lev. 19:2; 11:44); while God Himself, as the absolutely separate from evil, as repelling from Himself every possibility of sin or defilement, and as warring against these in every one of his creatures,2 obtains this title of ἅγιος by highest right of all (Lev. 10:3; 1 Sam. 2:2; Rev. 3:7; 4:8).

It is somewhat different with ἁγνός. Ἁγνεία (1 Tim. 4:12; 5:2) in the Definitions which go by Plato’s name too vaguely and too superficially explained (414 a) εὐλάβεια τῶν πρὸς τοὺς θεοὺς ἁμαρτημάτων· τῆς θεοῦ τιμῆς κατὰ φύσιν θεραπεία: too vaguely also by Clement of Alexandria as τῶν ἁμαρτημάτων ἀποχή, or again as φρονεῖν ὅσια (Strom. v. 1);3 is better defined as ἐπίτασις σωφροσύνης by Suidas (it is twice joined with σωφροσύνη in the Apostolic Fathers: Clement of Rome, 1 Cor. 21; Ignatius, Ephes. 20), as ἐλευθερία πάντος μολυσμοῦ σαρκὸς καὶ πνεύματος by Phavorinus. Ἁγνός (joined with ἀμίαντος, Clement of Rome, 1 Cor. 29) is the pure; sometimes only the externally or ceremonially pure, as in this line of Euripides, ἁγνὸς γάρ εἰμι χεῖρας, ἀλλ᾽ οὐ τὰς φρένας (Oresres, 1604; cf. Hippolytus, 316, 317, and ἁγνίζειν as == ‘expiare,’ Sophocles, Ajax, 640). This last word never rises higher in the Septuagint than to signify a ceremonial purification (Josh. 3:5; 2 Chron. 29:5; cf. 2 Macc. 1:33); neither does it rise higher in four out of the seven occasions on which it occurs in the N. T. (John 11:55; Acts 21:24, 26; 24:18, which is also true of ἁγνίσμος, Acts 21:26). Ἁγνός however signifies often the pure in the highest sense. It is an epithet frequently applied to heathen gods and goddesses, to Ceres, to Proserpine, to Jove (Sophocles, Philoct. 1273); to the Muses (Aristophanes, Ranoe, 875; Pindar, Olymp. vii. 60, and Dissen’s note); to the Sea- nymphs (Euripides, Iphig. in Aul. 982); above all in Homer to Artemis, the virgin goddess, and in Holy Scripture to God Himself (1 John 3:3). For this nobler use of ἁγνός in the Septuagint, where, however, it is excessively rare as compared to ἅγιος, see Ps. 11:7; Prov. 20:9. As there are no impurities like those fleshly, which defile the body and the spirit alike (1 Cor. 6:18, 19), so ἁγνός is an epithet predominantly employed to express freedom from these (Plutarch, Proec. Conj. 44; Quoest. Rom. 20; Tit. 2:5; cf. Herzog, Real-Encyclop. s. v. Keuschheit); while sometimes in a still more restricted sense it expresses, not chastity merely, but virginity; as in the oath taken by the priestesses of Bacchus (Demosthenes, Adv. Neoeram, 1371): εἰμὶ καθαρὰ καὶ ἁγνὴ ἀπ᾽ ἀνδρὸς συνουσίας: with which compare ἀκήρατος γάμων τε ἁγνός (Plato, Legg. viii. 840 e; and Euripides, Hippolytus, 1016); ἁγνεία too sometimes owns a similar limitation (Ignatius, ad Polyc. 5).

If what has been said is correct, Joseph, when tempted to sin by his Egyptian mistress (Gen. 39:7-12), approved himself ὅσιος, in reverencing those everlasting sanctities of the marriage bond, which God had founded, and which he could not violate without sinning against Him: “How can I do this great wickedness and sin against God?” he approved himself ὅγιος in that he separated himself from any unholy fellowship with his temptress; he approved himself ἁγνός in that he kept his body pure and undefiled.

1 Not altogether so in the Euthyphro, where Plato regards τὸ δίκαιον, or δικαιοσύνη, as the sum total of all virtue, of which ὁσιότης or piety is a part. In this Dialogue, which is throughout a discussion on the ὅσιον, Plato makes Euthyphro to say (12 e): τοῦτο τοίνυν ἔμοιγε δοκεῖ, ὦ Σώκρατες, τὸ μέρος τοῦ δικαίου εἶναι εὐσεβές τε καὶ ὅσιον, τὸ περὶ τὴν τῶν τῶν θεῶν θεραπείαν· τὸ δὲ περὶ τὴν τῶν ἀνθρώπων τὸ λοιπὸν εἶναι τοῦ δικαίου μέρος. Socrates admits and allows this; indeed, has himself forced him to it.

2 When Quenstedt defines the holiness of God as ‘summa omnis labia expers in Deo puritas,’ this, true as far as it goes, is not exhaustive. One side of this holiness, namely, its intolerance of unholiness and active war against it, is not brought out.

3 In the vestibule of the temple of aesculapius at Epidaurus were inscribed these lines, which rank among the noblest utterances of the ancient world. They are quoted by Theophrastus in a surviving fragment of his work, Περὶ Εὐσεβείας:

ἁγνὸν χρὴ ναιοῖο θυώδεος ἐντὸς ἰόντα

ἔμμεναι· ἁγνείη δ᾽ ἔστι φρονεῖν ὅσια.

[The following Strong's numbers apply to this section:G2413,G3741,G40,G53.]

Return to the Table of Contents