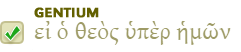

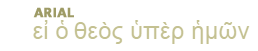

There has often been occasion to observe the manner in which Greek words taken up into Christian use are glorified and transformed, seeming to have waited for this adoption of them, to come to their full rights, and to reveal all the depth and the riches of meaning which they contained, or might be made to contain. Χάρις is one of these. It is hardly too much to say that the Greek mind has in no word uttered itself and all that was at its heart more distinctly than in this; so that it will abundantly repay our pains to trace briefly the steps by which it came to its highest honours. Χάρις, connected with χαίρειν, is first of all that property in a thing which causes it to give joy to the hearers or beholders of it, as Plutarch (Cum Princ. Phil. Diss. 3) has rightly explained it, χαρᾶς γὰρ οὐδὲν οὕτως γονιμόν ἐστιν ὡς χάρις (cf. Pott, Etym. Forsch. vol. ii. part 1, p. 217); and then, seeing that to a Greek there was nothing so joy-inspiring as grace or beauty, it implied the presence of this, the German ‘Anmuth’; thus Homer, Od. ii. 12; vi. 237; Euripides, Troad. 1108, παρθένων χάριτες; Lucian, Zeux. 2. χάρις Αττική. It has often this use in the Septuagint (

But χάρις after a while came to signify not necessarily the grace or beauty of a thing, as a quality appertaining to it; but the gracious or beautiful thing, act, thought, speech, or person it might be, itself—the grace embodying and uttering itself, where there was room or call for this, in gracious outcomings toward such as might be its objects; not any longer ‘favour’ in the sense of beauty, but ‘the favour’; for our word here a little helps us to trace the history of the Greek. So continually in classical Greek we have χάριν ἀπαιτεῖν, λαμβάνειν, δοῦναι; so in the Septuagint (

Already, it is true, if not there, yet in another quarter there were preparations for this glorification of meaning to which χάρις was destined. These lay in the fact that already in the ethical terminology of the Greek schools χάρις implied ever a favour freely done, without claim or expectation of return—the word being thus predisposed to receive its new emphasis, its religious, I may say its dogmatic, significance; to set forth the entire and absolute freeness of the lovingkindness of God to men. Thus Aristotle, defining χάρις, lays the whole stress on this very point, that it is conferred freely, with no expectation of return, and finding its only motive in the bounty and free-heartedness of the giver (Rhet. ii. 7): ἔστω δὴ χάρις, καθ᾽ ἣν ὁ ἔχων λέγεται χάριν ὑπουργεῖν τῷ δεομένῳ, μὴ ἀντὶ τινὸς, μηδ᾽ ἵνα τι αὐτῷ τῷ ὑπουργοῦντι, ἀλλ᾽ ἵνα ἐκείνῳ τι. Agreeing with this we have χάρις καὶ δωρεά, Polybius, i. 31. 6 (cf.

But while χάρις has thus reference to the sins of men. and is that glorious attribute of God which these sins call out and display, his free gift in their forgiveness, ἔλεος has special and immediate regard to the misery which is the consequence of these sins, being the tender sense of this misery displaying itself in the effort, which only the continued perverseness of man can hinder or defeat, to assuage and entirely remove it; so Bengel well: ‘Gratia tollit culpam, misericordia miseriam.’ But here, as in other cases, it may be worth our while to consider the anterior uses of this word, before it was assumed into this its highest use as the mercy of Him, whose mercy is over all his works. Of ἔλεος we have this definition in Aristotle (Rhet. ii. 8): ἔστω δὴ ἔλεος, λύπη τις ἐπὶ φαινομένῳ κακῷ φθαρτικῷ καὶ λυπηρῷ, τοῦ ἀναξίου τυγχάνειν, ὃ κἂν αὐτὸς προσδοκήσειεν ἂν παθεῖν, ἢ τῶν αὐτοῦ τινά. It will be at once perceived that much will have here to be modified. and something removed, when we come to speak of the ἔλεος of God. Grief does not and cannot touch Him, in whose presence is fulness of joy; He does not demand unworthy suffering (λύπη ὡς ἐπὶ ἀναξίως κακοπαθοῦντι, which is the Stoic definition of ἔλεος, Diogenes Laërtius, vii. 1. 63),1 to move Him, seeing that absolutely unworthy suffering there is none in a world of sinners; neither can He, who is lifted up above all chance and change, contemplate, in beholding misery, the possibility of being Himself involved in the same. It is nothing wonderful that the Manichaeans and others who desired a God as unlike man as possible, cried out against the attribution of ἔλεος to Him; and found here a weapon of their warfare against that Old Testament, whose God was not ashamed to proclaim Himself a God of pity and compassion (

In the Divine mind, and in the order of our salvation as conceived therein, the ἔλεος precedes the χάρις. God so loved the world with a pitying love (herein was the ἔλεος), that He gave his only begotten Son (herein the χάρις), that the world through Him might be saved (cf.

1 So Cicero (Tusc. iv. 8. 18): ‘Misericordia est aegritudo ex miseriâ alterius injuriâ laborantis. Nemo enim parricidae aut proditoris supplicio misericordiâ commovetur.’

[The following Strong's numbers apply to this section:G1656,G5485.]

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |