Righteousness:

See JUSTIFICATION.

Righteousness:

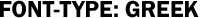

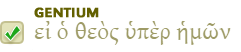

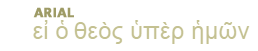

ri'-chus-nes (tsaddiq, adjective, "righteous," or occasionally "just" tsedheq, noun, occasionally =" riahteousness," occasionally =" justice"; dikaios, adjective, dikaiosune, noun, from dike, whose first meaning seems to have been "custom"; the general use suggested conformity to a standard: righteousness, "the state of him who is such as he ought to be" (Thayer)):

1. Double Aspect of Righteousness: Changing and Permanent

2. Social Customs and Righteousness

3. Changing Conception of Character of God: Obligations of Power

4. Righteousness as Inner

5. Righteousness as Social

6. Righteousness as Expanding in Content with Growth in Ideals of Human Worth

LITERATURE

1. Double Aspect of Righteousness: Changing and Permanent:

In Christian thought the idea of righteousness contains both a permanent and a changing element. The fixed element is the will to do right; the changing factor is the conception of what may be right at different times and under different circumstances. Throughout the entire course of Christian revelation we discern the emphasis on the first factor. To be sure, in the days of later Pharisaism righteousness came to be so much a matter of externals that the inner intent was often lost sight of altogether (Mt 23:23); but, on the whole and in the main, Christian thought in all ages has recognized as the central element in righteousness the intention to be and do right. This common spirit binds together the first worshippers of God and the latest. Present-day conceptions of what is right differ by vast distances from the conceptions of the earlier Hebrews, but the intentions of the first worshippers are as discernible as are those of the doers of righteousness in the present day.

2. Social Customs and Righteousness:

There seems but little reason to doubt that the content of the idea of righteousness was determined in the first instance by the customs of social groups. There are some, of course, who would have us believe that what we experience as inner moral sanction is nothing but the fear of consequences which come through disobeying the will of the social group, or the feeling of pleasure which results as we know we have acted in accordance with the social demands. At least some thinkers would have us believe that this is all there was in moral feeling in the beginning. If a social group was to survive it must lay upon its individual members the heaviest exactions. Back of the performance of religious rites was the fear of the group that the god of the group would be displeased if certain honors were not rendered to him. Merely to escape the penalties of an angry deity the group demanded ceremonial religious observances. From the basis of fear thus wrought into the individuals of the group have come all our loftier movements toward righteousness.

It is not necessary to deny the measure of truth there may be in this account. To point out its inadequacy, however, a better statement would be that from the beginning the social group utilized the native moral feeling of the individual for the defense of the group. The moral feeling, by which we mean a sense of the difference between right and wrong, would seem to be a part of the native furnishing of the mind. It is very likely that in the beginning this moral feeling was directed toward the performance of the rites which the group looked upon as important.

See ALMS.

As we read the earlier parts of the Old Testament we are struck by the fact that much of the early Hebrew morality was of this group kind. The righteous man was the man who performed the rites which had been handed down from the beginning (De 6:25). The meaning of some of these rites is lost in obscurity, but from a very early period the characteristic of Hebrew righteousness is that it moves in the direction of what we should call today the enlargement of humanity. There seemed to be at work, not merely the forces which make for the preservation of the group, not merely the desire to please the God of the Hebrews for the sake of the material favors which He might render the Hebrews, but the factors which make for the betterment of humanity as such. As we examine the laws of the Hebrews, even at so late a time as the completion of the formal Codes, we are indeed struck by traces of primitive survivals (Nu 5:11-31). There are some injunctions whose purpose we cannot well understand. But, on the other hand, the vast mass of the legislation had to do with really human considerations. There are rules concerning Sanitation (Le 13), both as it touches the life of the group and of the individual; laws whose mastery begets emphasis, not merely upon external consequences, but upon the inner result in the life of the individual (Ps 51:3); and prohibitions which would indicate that morality, at least in its plainer decencies, had come to be valued on its own account. If we were to seek for some clue to the development of the moral life of the Hebrews we might well find it in this emphasis upon the growing demands of human life as such. A suggestive writer has pointed out that the apparently meaningless commandment, "Thou shalt not boil a kid in its mother's milk" (Ex 23:19), has back of it a real human purpose, that there are some things which in themselves are revolting apart from any external consequences (see also Le 18).

3. Changing Conception of Character of God: Obligations of Power:

An index of the growth of the moral life of the people is to be found in the changing conception of the character of God. We need not enter into the question as to just where on the moral plane the idea of the God of the Hebrews started, but from the very beginning we see clearly that the Hebrews believed in their God as one passionately devoted to the right (Ge 18:25). It may well be that at the start the God of the Hebrews was largely a God of War, but it is to be noticed that His enmity was against the peoples who had little regard for the larger human considerations. It has often been pointed out that one proof of the inspiration of the Scriptures is to be found in their moral superiority to the Scriptures of the peoples around about the Hebrews. If the Hebrew writers used material which was common property of Chaldeans, Babylonians, and other peoples, they nevertheless used these materials with a moral difference. They breathed into them a moral life which forever separates them from the Scriptures of other peoples. The marvel also of Hebrew history is that in the midst of revoltingly immoral surroundings the Hebrews grew to such ideals of human worth. The source of these ideals is to be found in their thougth of God. Of course, in moral progress there is a reciprocal effect; the thought of God affects the thought of human life and the thought of human life affects the thought of God; but the Hebrews no sooner came to a fresh moral insight than they made their moral discovery a part of the character of God. From the beginning, we repeat, the God of the Hebrews was a God directed in His moral wrath against all manner of abominations, aberrations and abnormalities. The purpose of God, according to the Hebrews, was to make a people "separated" in the sense that they were to be free from anything which would detract from a full moral life (Le 20:22).

We can trace the more important steps in the growth of the Hebrew ideal. First, there was an increasingly clear discernment that certain things are to be ruled out at once as immoral. The primitive decencies upon which individual and social life depended were discerned at an early period (compare passages in Leviticus cited above). Along with this it must be admitted there was a slower approach to some ideals which we today consider important, the ideals of the marriage relations for example (De 24:1,2). Then there was a growing sense of what constitutes moral obligation in the discharge of responsibilities upon the part of men toward their fellows (Isa 5:8,23). There was increasing realization also of what God, as a moral Being, is obligated to do. The hope of salvation of nations and individuals rests at once upon the righteousness of God.

By the time of Isaiah the righteousness of God has come to include the obligations of power (Isa 63:1). God will save His people, not merely because He has promised to save them, but because He must save them (Isa 42:6). The must is moral. If the people of Israel show themselves unworthy, God must punish them; but if a remnant, even a small remnant, show themselves faithful, God must show His favor toward them. Moral worth is not conceived of as something that is to be paid for by external rewards, but if God is moral He must not treat the righteous and the unrighteous alike. This conception of what God must do as an obligated Being influences profoundly the Hebrew interpretation of the entire course of history (Isa 10:20,21).

Upon this ideal of moral obligation there grows later the thought of the virtue of vicarious suffering (Isaiah 53). The sufferings of the good man and of God for those who do not in themselves deserve such sufferings (for them) are a mark of a still higher righteousness (see HOSEA). The movement of the Scriptures is all the way from the thought of a God who gives battle for the right to the thought of a God who receives in Himself the heaviest shocks of that battle that others may have opportunity for moral life.

These various lines of moral development come, of course, to their crown in the New Testament in the life and death of Christ as set before us in the Gospels and interpreted by the apostles. Jesus stated certain moral axioms so clearly that the world never will escape their power. He said some things once and for all, and He did some things once and for all; that is to say, in His life and death He set on high the righteousness of God as at once moral obligation and self-sacrificing love (Joh 3:16) and with such effectiveness that the world has not escaped and cannot escape this righteous influence (Joh 12:32). Moreover, the course of apostolic and subsequent history has shown that Christ put a winning and compelling power into the idea of righteousness that it would otherwise have lacked (Ro 8:31,32).

4. Righteousness as Inner:

The ideas at work throughout the course of Hebrew and Christian history are, of course, at work today. Christianity deepens the sense of obligation to do right. It makes the moral spirit essential. Then it utilizes every force working for the increase of human happiness to set on high the meaning of righteousness. Jesus spoke of Himself as "life," and declared that He came that men might have life and have it more abundantly (Joh 10:10). The keeping of the commandments plays, of course, a large part in the unfolding of the life of the righteous Christian, but the keeping of the commandments is not to be conceived of in artificial or mechanical fashion (Lu 10:25-37). With the passage of the centuries some commandments once conceived of as essential drop into the secondary place, and other commandments take the controlling position. In Christian development increasing place is given for certain swift insights of the moral spirit. We believe that some things are righteous because they at once appeal to us as righteous. Again, some other things seem righteous because their consequences are beneficial, both for society and for the individual. Whatever makes for the largest life is in the direction of righteousness. In interpreting life, however, we must remember the essentially Christian conception that man does not live through outer consequences alone. In all thought of consequences the chief place has to be given to inner consequences. By the surrender of outward happiness and outward success a man may attain inner success. The spirit of the cross is still the path to the highest righteousness.

5. Righteousness as Social:

The distinctive note in emphasis upon righteousness in our own day is the stress laid upon social service. This does not mean that Christianity is to lose sight of the worth of the individual in himself. We have come pretty clearly to see that the individual is the only moral end in himself. Righteousness is to have as its aim the upbuilding of individual lives. The commandments of the righteous life are not for the sake of society as a thing in itself. Society is nothing apart from the individuals that compose it; but we are coming to see that individuals have larger relationships than we had once imagined and greater responsibilities than we had dreamed of. The influence of the individual touches others at more points than we had formerly realized. We have at times condemned the system of things as being responsible for much human misery which we now see can be traced to the agency of individuals. The employer, the day-laborer, the professional man, the public servant, all these have large responsibilities for the life of those around. The unrighteous individual has a power of contaminating other individuals, and his deadliness we have just begun to understand. All this is receiving new emphasis in our present-day preaching of righteousness. While our social relations are not ends in themselves, they are mighty means for reaching individuals in large numbers. The Christian conception of redeemed humanity is not that of society as an organism existing on its own account, but that of individuals knit very closely together in their social relationships and touching one another for good in these relationships (1Co 1:2; Re 7:9,10). If we were to try to point out the line in which the Christian doctrine of righteousness is to move more and more through the years, we should have to emphasize this element of obligation to society. This does not mean that a new gospel is to supersede the old or even place itself alongside the old. It does mean that the righteousness of God and the teaching of Christ and the cross, which are as ever the center of Christianity, are to find fresh force in the thought of the righteousness of the Christian as binding itself, not merely by commandments to do the will of God in society, but by the inner spirit to live the life of God out into society.

6. Righteousness as Expanding in Content with Growth in Ideals of Human Worth:

In all our thought of righteousness it must be borne in mind that there is nothing in Christian revelation which will tell us what righteousness calls for in every particular circumstance. The differences between earlier and later practical standards of conduct and the differences between differing standards in different circumstances have led to much confusion in the realm of Christian thinking. We can keep our bearing, however, by remembering the double element in righteousness which we mentioned in the beginning; on the one hand, the will to do right, and, on the other, the difficulty of determining in a particular circumstance just what the right is. The larger Christian conceptions always have an element of fluidity, or, rather, an element of expansiveness. For example, it is clearly a Christian obligation to treat all men with a spirit of good will or with a spirit of Christian love. But what does love call for in a particular case? We can only answer the question by saying that love seeks for whatever is best, both for him who receives and for him who gives. This may lead to one course of conduct in one situation and to quite a different course in another. We must, however, keep before us always the aim of the largest life for all persons whom we can reach. Christian righteousness today is even more insistent upon material things, such as sanitary arrangements, than was the Code of Moses. The obligation to use the latest knowledge for the hygienic welfare is just as binding now as then, but "the latest knowledge" is a changing term. Material progress, education, spiritual instruction, are all influences which really make for full life.

Not only is present-day righteousness social and growing; it is also concerned, to a large degree, with the thought of the world which now is. Righteousness has too often been conceived of merely as the means of preparing for the life of some future Kingdom of Heaven. Present-day emphasis has not ceased to think of the life beyond this, but the life beyond this can best be met and faced by those who have been in the full sense righteous in the life that now is. There is here no break in true Christian continuity. The seers who have understood Christianity best always have insisted that to the fullest degree the present world must be redeemed by the life-giving forces of Christianity. We still insist that all idea of earthly righteousness takes its start from heavenly righteousness, or, rather, that the righteousness of man is to be based upon his conception of the righteousness of God. Present-day thinking concerns itself largely with the idea of the Immanence of God. God is in this present world. This does not mean that there may not be other worlds, or are not other worlds, and that God is not also in those worlds; but the immediate revelation of God to us is in our present world. Our present world then must be the sphere in which the righteousness of God and of man is to be set forth. God is conscience, and God is love. The present sphere is to be used for the manifestation of His holy love. The chief channel through which that holy love is to manifest itself is the conscience and love of the Christian believer. But even these terms are not to be used in the abstract. There is an abstract conscientiousness which leads to barren living: the life gets out of touch with things that are real. There is an experience of love which exhausts itself in well-wishing. Both conscience and love are to be kept close to the earth by emphasis upon the actual realities of the world in which we live.

LITERATURE.

G. B. Stevens, The Christian Doctrine of Salvation; A. E. Garvie, Handbook of Christian Apologetics; Borden P. Bowne, Principles of Ethics; Newman Smyth, Christian Ethics; A. B. Bruce, The Kingdom of God; W. N. Clarke, The Ideal of Jesus; H. C. King, The Ethics of Jesus.

Written by Francis J. McConnell

Righteousness:

Righteousness: God Loves

Righteousness: God Looks For

Righteousness: Christ

Is the Sun of

Loves

Was girt with

Put on, as breast-plate

Was sustained by

Preached

Fulfilled all

Is made to his people

Is the end of the law for

Has brought in everlasting

Shall judge with

Psa 72:2; Isa 11:4; Act 17:31; Rev 19:11

Shall reign in

Shall execute

Righteousness: The blessing of God is not to be attributed to our works of

Righteousness: Saints

Have, in Christ

Have, imputed

Are covered with the robe of

Receive, from God

Are renewed in

Are led in the paths of

Are servants of

Characterised by

Know

Do

Work, by faith

Follow after

Put on

Wait for the hope of

Pray for the spirit of

Hunger and thirst after

Walk before God in

Offer the sacrifice of

Put no trust in their own

Count their own, as filthy rags

Should seek

Should live in

Should serve God in

Should yield their members as instruments of

Should yield their members servants to

Should have on the breast-plate of

Shall receive a crown of

Shall see God's face in

Righteousness: An Evidence of the New Birth

Righteousness: The Kingdom of God Is

Righteousness: The Fruit of the Spirit Is in All

Righteousness: The Scriptures Instruct In

Righteousness: Judgments Designed to Lead To

Righteousness: Chastisements Yield the Fruit Of

Righteousness: Has No Fellowship with Unrighteousness

Righteousness: Ministers Should

Be preachers of

Reason of

Follow after

Be clothed with

Be armed with

Pray for the fruit of, in their people

Righteousness: Judgment Should Be Executed In

Righteousness: They Who Walk In, and Follow

Are righteous

Are the excellent of the earth

Are accepted with God

Are loved by God

Are blessed by God

Are heard by God

Are objects of God's watchful care

Job 36:7; Psa 34:15; Pro 10:3; 1Pe 3:12

Are tried by God

Are exalted by God

Dwell in security

Are bold as a lion

Are delivered out of all troubles

Are never forsaken by God

Are abundantly provided for

Are enriched

Think and desire good

Know the secret of the Lord

Have their prayers heard

Psa 34:17; Pro 15:29; 1Pe 3:12

Have their desires granted

Find it with life and honour

Shall hold on their way

Shall never be moved

Psa 15:2,5; 55:22; Pro 10:30; 12:3

Shall be ever remembered

Shall flourish as a branch

Righteousness: Shall Be Glad in the Lord

Righteousness: The Work Of, Shall Be Peace

Righteousness: The effect of, shall be quietness and assurance for ever

Righteousness: Is a Crown of Glory to the Aged

Righteousness: The Wicked

Are far from

Are free from

Are enemies of

Leave off

Follow not after

Do not

Do not obey

Love lying rather than

Make mention of God, not it

Though favoured, will not learn

Speak contemptuously against those who follow

Hate those who follow

Slay those who follow

Psa 37:32; 1Jo 3:12; Mat 23:35

Should break off their sins by

Should awake to

Should sow to themselves in

Vainly wish to die as those who follow

Righteousness: Nations Exalted By

Righteousness: Blessedness Of

Having imputed, without works

Doing

Hungering and thirsting after

Suffering for

Being persecuted for

Turning others to

| 1 | Strong's Number: g1343 | Greek: dikaiosune |

Righteousness:

is "the character or quality of being right or just;" it was formerly spelled "rightwiseness," which clearly expresses the meaning. It is used to denote an attribute of God, e.g., Rom 3:5, the context of which shows that "the righteousness of God" means essentially the same as His faithfulness, or truthfulness, that which is consistent with His own nature and promises; Rom 3:25, 26 speaks of His "righteousness" as exhibited in the Death of Christ, which is sufficient to show men that God is neither indifferent to sin nor regards it lightly. On the contrary, it demonstrates that quality of holiness in Him which must find expression in His condemnation of sin.

"Dikaiosune is found in the sayings of the Lord Jesus,

(a) of whatever is right or just in itself, whatever conforms to the revealed will of God, Mat 5:6, 10, 20; Jhn 16:8, 10;

(b) whatever has been appointed by God to be acknowledged and obeyed by man. Mat 3:15; 21:32;

(c) the sum total of the requirements of God, Mat 6:33;

(d) religious duties, Mat 6:1 (distinguished as almsgiving, man's duty to his neighbor, Mat 6:2-4, prayer, his duty to God, Mat 6:5-15, fasting, the duty of self-control, Mat 6:16-18).

"In the preaching of the Apostles recorded in Acts the word has the same general meaning. So also in Jam 1:20; 3:18, in both Epp. of Peter, 1st John and the Revelation. In 2Pe 1:1, 'the righteousness of our God and Savior Jesus Christ,' is the righteous dealing of God with sin and with sinners on the ground of the Death of Christ. 'Word of righteousness,' Hbr 5:13, is probably the gospel, and the Scriptures as containing the gospel, wherein is declared the righteousness of God in all its aspects.

"This meaning of dikaiosune, "right action", is frequent also in Paul's writings, as in all five of its occurrences in Rom. 6; Eph 6:14, etc. But for the most part he uses it of that gracious gift of God to men whereby all who believe on the Lord Jesus Christ are brought into right relationship with God. This righteousness is unattainable by obedience to any law, or by any merit of man's own, or any other condition than that of faith in Christ.... The man who trusts in Christ becomes 'the righteousness of God in Him,' 2Cr 5:21, i.e., becomes in Christ all that God requires a man to be, all that he could never be in himself. Because Abraham accepted the Word of God, making it his own by that act of the mind and spirit which is called faith, and, as the sequel showed, submitting himself to its control, therefore God accepted him as one who fulfilled the whole of His requirements, Rom 4:3....

"Righteousness is not said to be imputed to the believer save in the sense that faith is imputed ('reckoned' is the better word) for righteousness. It is clear that in Rom 4:6,11, 'righteousness reckoned' must be understood in the light of the context, 'faith reckoned for righteousness,' Rom 4:3, 5, 9, 22. 'For' in these places is eis, which does not mean 'instead of,' but 'with a view to.' The faith thus exercised brings the soul into vital union with God in Christ, and inevitably produces righteousness of life, that is, conformity to the will of God." *

[* From Notes on Galatians, by Hogg and Vine, pp. 246, 247.]

| 2 | Strong's Number: g1345 | Greek: dikaioma |

Righteousness:

is the concrete expression of "righteousness:" see JUSTIFICATION, A, No. 2.

Note: In Hbr 1:8, AV, euthutes, "straightness, uprightness" (akin to euthus "straight, right"), is translated "righteousness" (RV, "uprightness;" AV, marg., "rightness, or straightness").

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

Loading

Loading

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |